Ascanius; or, the Young

Adventurer

BOOK I

Containing an Impartial Account of the Rebellion

in

|

T |

he family of the Stuarts is of great antiquity.

The earliest accounts declare them from a thane of Lochaber. But antiquity is

ever involved in absurdity. However, we are certain that the first of them who

reigned in

Upon the death of Elizabeth Queen of

This ancient and noble family governed these realms, in an

uninterrupted line, down to James VII. This unfortunate prince had a blind

attachment for the Popish religion. During his administration he openly

discovered it, and exercised, for a time, amongst his subjects, all those tyrannical

measures which that religion naturally instigates those princes, who are its

votaries, to pursue. His eldest daughter Mary, was given in marriage to William

Prince of

The first interruption, we see then, in the

lineal descent of the family of Stuarts, in their succession to the crowns of

While the attention of

Accordingly, upon the 15th of July, 1745, Prince

Charles, being furnished with a supply of money and arms from the French

ministry, embarked at Port Lazare, in Britanny, for

The frigate arrived among the Scottish isles, and

after hovering about for several days, made to the coast of

By this time the government was informed of his being in the

Highlands, and sent strict orders to Sir John Cope, generalisimo of the king's

forces in Scotland, to take all possible care to prevent him from making his

party formidable, and if possible to take him alive or dead; and as

an inducement to this a reward of £30,000 Sterling was set on his head.

Before the end of August, two companies of General Sinclair's regiment

being sent to reconnoitre the Highlanders, were most of them made prisoners, as

was soon after Captain Swethenham of Guise's foot. This gentleman being

released on his parole, gave the government the first circumstantial account of

the number and condition of the

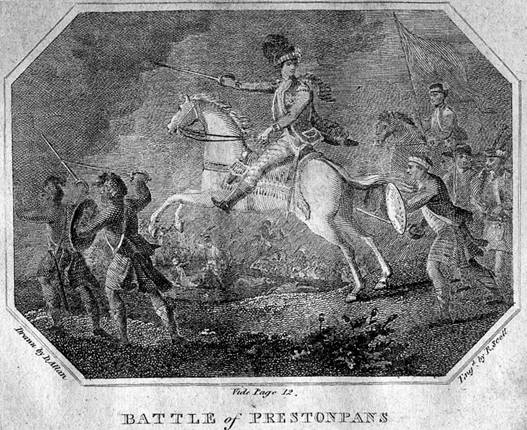

Ascanius now prepared to march southward, with a

view of taking the city of Edinburgh; while, in the meantime, Cope having

collected all the king's forces in Scotland, and armed the militia, marched for the Highlands in quest of Ascanius;

who, not choosing to risk a battle in his infant state of affairs, gave the old

general the slip over the mountains, and (September 4) entered Perth without

resistance. The news being carried to Cope, who had got to Inverness, after a

very fatiguing march, he saw no other remedy but to march back, though not the

same way he came; accordingly, he ordered transport ships to meet him at

While both parties were thus advancing towards

the metropolis, the inhabitants were preparing for a vigorous resistance: But

the Prince having many friends in the city, no sooner came near it, than a

treaty of surrender was entered upon, and on the 17th the provost admitted him

into it; however, the brave, though very old, general Guest, retired with

a few regulars into the castle, which he held for the king. While the Prince

was entering the city, Cope was disembarking his troops at Dunbar, within

two days march of

The

following circumstances of his death are narrated by P. Doddridge, DD and may

be relied on as authentic.

"On Friday, September 20, 1745,

(the day before the battle,) when the whole army was drawn up, I think about

noon, the Colonel rode through all the ranks of his own regiment, addressing

them at once in the most respectful and animating manner, both as soldiers and

as Christians, to engage them to exert themselves courageously in the service

of their country, and to neglect nothing that might have a tendency to prepare

them for whatever should be the event of the battle.

"They seemed much affected with the address, and expressed a very

ardent desire of attacking the enemy immediately. He earnestly pressed it on

the commanding officer, both as the soldiers were then in better spirits than

it could be supposed they would be after having passed the night under arms;

and also as the circumstance of making an attack would be some encouragement to

them, and probably some terror to the enemy, who would have had the disadvantage

of standing on the defence. He also apprehended, that by marching to meet them,

some advantage might have been secured with regard to the ground; with which,

it is natural to imagine, he must have been perfectly acquainted, as it lay

just at his own door, and he had rode over it so many hundred times. But this

was overruled, as it also was in the disposition of the cannon, which he

would have had planted in the centre of our small army, rather than just before

his regiment, which was in the right wing; where he was apprehensive, that the

horses, which had not been in any engagement before, might be thrown into some

disorder by the discharge so very near them.

"When he found that he could not carry either of these points,

nor some others, which out of regard to the common safety be insisted upon with

some unusual earnestness, he dropped some intimations of the consequences which

he apprehended, and which did in fact follow; and submitting to Providence,

spent the remainder of the day in making as good disposition as circumstances

would allow.

"He continued all night under arms, wrapped up in his cloak, and

generally sheltered under a rick of barley which happened to be in the field.

About three in the morning, he called his domestic servants to him, of whom

there were four in waiting.

"He then dismissed three of them, with most affectionate

Christian advice, and such solemn charges relating to the performance of their

duty and the care of their souls, as seemed plainly to intimate, that he

apprehended it at least very probably he was now taking his last farewell of

them.

"The army was alarmed by break of day, by the noise of the

Rebels' approach, and the attack was made before sun-rise, yet when it was

light enough to discern what passed. As soon as the enemy came within gun-shot,

they made a furious fire; and it is said that the dragoons, which constituted

the left wing, immediately fled. The Colonel, at the beginning of the onset,

which in the whole lasted but a few minutes, received a wound by a bullet in

his left breast, which made him give a sudden spring in his saddle; upon which

his servant who had led the horse, would have persuaded him to retreat; but he

said, it was only a wound in the flesh; and fought on, though he presently

after received a shot in his right thigh. In the meantime, it was discerned

that some of the enemy fell by him and particularly one man, who had made him a

treacherous visit but a few days before, with great professions of zeal for the

present establishment.

"The Colonel was for a few moments supported by his men, and

particularly by that worthy person Lieutenant Colonel Whitney, who was shot

through the arm here, and few months after fell nobly in the battle of

"The moment he fell, another Highlander, whose name was McNaught,

and who was executed about a year after, gave him a stroke, either with a broad

sword or a Lochaber-axe, on the hinder part of his head, which was the mortal

blow. All that his faithful attendant saw farther at that time was, that as his

hat was fallen off, he took it in his left hand, and waved it as a signal to

him to retreat; and added, what were the last words he ever heard him speak,

"Take care of yourself:" Upon which the servant retired, and

immediately fled to a mill, at the distance of about two miles from the spot of

ground on which the colonel fell, where he changed his dress, and, disguised

like a miller's servant, returned with a cart as soon as possible, which was

not till near two hours after the engagement.

"The hurry of the action was then pretty well over, and he found

his much-honoured master, not only plundered of his watch, and other things of

value, but also stripped of his upper garments and boots, yet still breathing;

and though not capable of speech, yet on taking him up, he opened his eyes;

which makes it something questionable whether he were altogether insensible. In

this condition, and in this manner, he conveyed him to the church of Tranent,

from whence he was immediately taken into the minister's house, and laid in bed,

where he continued breathing, and frequently groaning, till about eleven in the

forenoon, when he took his final leave of pain and sorrow, and undoubtedly rose

to those distinguished glories which are reserved for those who have been so

eminently and remarkably faithful unto death.

"From the moment in which he fell it was not longer a battle, but

a rout and carnage. The cruelties which the rebels inflicted on some of the

king's troops, after they had asked quarter, were dreadfully legible on the

countenances of many who survived it. They entered Colonel Gardiner's house

before he was carried off from the field, and plundered it of everything of

value, to the very curtains of the beds, and hangings of the rooms. His papers

were all thrown into the wildest disorder, and his house made a hospital for

the reception of those who were wounded in the action.

"The remains of this Christian hero were interred the Tuesday

following, September 24, at the parish

Many other principal officers were desperately wounded, and a

considerable number of the common men made prisoners. All the cannon, tents,

&c. of the vanquished, were taken.

Cope had the good fortune to escape to Berwick, with the Earls of

From this victory Ascanius reaped considerable advantages. It inspired

his followers with courage, intimidated his enemies, and many, who before that

time acted upon the reserve, now crowded to his standard. This victory, also

put his army in possession of fire-arms and ammunition, with which they were

formerly ill provided. He now returned in triumph to

We cannot help observing the conduct of the French court on this

occasion; when they heard he had gained a victory, they supplied him with

money, artillery and ammunition; his interest with them seemed to depend on the

success of his arms.

Ascanius did not find so many in the kingdom espouse his cause as he

was made to believe. The greater part of the kingdom did not favour his family

and pretensions; but they were unarmed and undisciplined, and therefore could

make no resistance.

And even in the

At the same time, Duncan Forbes, Esq. Lord President of the Court of

Session in Scotland, particularly distinguished himself there, by his zeal for

the Georgian interest; and it was principally by his means, that a considerable

body of Highlanders and other Scots were raised, under the command of the Earl

of Loudon, for the security of the forts of Inverness, Augustus and William, a

chain of fortified places commanding the north of Scotland.

But notwithstanding all these preparations, the intrepid Ascanius

resolved to pursue his designs through all obstacles. (Nov. 1.) He went from

Edinburgh to the camp at Dalkeith, from whence he daily dispatched his agents

into England, and received intelligence of what was doing there both by his

friends and enemies; and, though he had the mortification to find, contrary to

the assurances he had received, that the former were but few, yet he still

inflexibly resolved to push on the daring attempt, having only, as he publicly

signified, a crown or a coffin in view. He hoped that, by his presence in

With these views, and in this resolute disposition, he began his march

for Carlisle, with an army not exceeding 6700 effective men; a small number for

such an expedition; but he relied much on English reinforcements, and more, on

a timely descent by the French in the south; for in case of such a diversion,

nothing could have effectually obstructed his march to London. The principal

persons in his army were, the Duke of Perth, general; Lord George Murray,

lieutenant-general; Lord Elcho, son to the Earl of Wemyss, colonel of the

life-guards; the Earl of Kilmarnock, colonel of a regiment mounted and accoutered

as hussars; Lord Portsligo, general of the horse; the Lords Nairn, Ogilvie,

Dundee, and Balmerino; Messrs. Sheridan and Sullivan, Irish gentlemen; General

McDonald, his aid-de-camp; John Murray of Broughton, Esq. his secretary; and

many others.

On the 6th November, the Prince's army passed the Tweed, and entered

And now the progress of Ascanius had thrown all

Meantime, the young Adventurer advanced with prodigious celerity,

while the attention of both kingdoms was fixed on the expected approaching

action. On the 20th, our Adventurer left Carlisle, from whence be proceeded to

Thus cheered, the adventurers still went southward, until they came

within the borders of Staffordshire, where the Duke lay with an army to

intercept them; Wade was also marching after them through

I must not forget to mention, that in every city and market-town

through which Ascanius passed, he took possession of it for his father, by

proclaiming him; for instance, in Carlisle, Penrith, Kendal,

December 2nd, Ascanius was at Leek in the moorlands of Staffordshire,

next day at Ashburn in the

Hereupon a council of war was called, at which the chiefs spoke very

freely, and strenuously insisted on the army's returning to Scotland by the way

he came; urging, that they might get through Derby and Stafford before the

Duke, on the south side of them, could know they had begun to return; and that,

as Wade lay directly north from them, they doubted not of again giving him the

slip, and reaching Carlisle before he could obstruct their flight. -- To this

advice Ascanius consented, still comforting himself with hopes that

As a delay of a day or two must have rendered the retreat of Ascanius

and his troops impracticable, they stayed at

Lord Lewis Gordon, brother to the Duke of Gordon, who remained in

On the other hand, the Earl of Loudon was equally

active in spiriting up the clans in the Georgian interest; he raised

considerable supplies among the McLeods, Grants, Monros, Sutherlands, and

Gunns, and at last he had above 2300 effective men; with these he forced the

son of Lord Lovat to retire from before Fort Augustus, which he had besieged

with a considerable body of Frasers, a clan of which his father was chief. The

city of

Let us now return into

Macclesfield, where, as we have observed, the English arrived on the

10th, is but a day's march from Manchester, from whence Ascanius marched that

day, resting his troops there only one night; the fickle inhabitants,

perceiving fortune seemed to frown on the adventurers, whom they had joyfully

received a few days before, now gave the troops several rude marks of a very

different spirit; this Ascanius so highly resented, that he made the people pay

him £2500, to save them from being plundered, before he left the town; however,

in consideration of the many friends he still had there, he promised repayment

when the kingdom should be recovered to his family, of which he did not

despair.

On the 11th, the adventurers, marched further northward, and came to

Wigan, and next day to

However, on the 14th, upon better information, the Duke ordered

Oglethorpe to continue the pursuit, whilst himself followed as fast as

possible. On the 15th Ascanius arrived at Kendal in Westmoreland, and marched

next day for Penrith in

Next morning Ascanius arrived at

The 20th, the English advanced to Hesket, within a short day's march

of

This small garrison, animated with a greater share of courage and fidelity

to the cause they had embraced, than of prudence or human foresight, resolved

obstinately to defend the city. They were greatly spirited up by Mr. John

Hamilton of Aberdeenshire, their governor, who represented unto them,

"That it was both their duty, and the most honourable thing they could do,

to defend the place to the last extremity. The place is," said he,

"both by art and nature, pretty strong, and we have artillery enough: the

English have no cannon, nor can speedily bring any hither, so that we may,

doubtless, hold out a month; mean time, Ascanius will certainly do all in his

power to relieve us, and who knows how for it may be yet in his power? Besides,

the English may not, perhaps, when they see us resolute, stay to besiege us in

form, but follow our friends into Scotland; in which case you may do Ascanius

some service, by employing part of the enemy's troops to look after us, and

thereby, in some measure, pave the way to his being a match for them in the

field; whereas, at present, he is in danger of being overwhelmed by

numbers."

On the 22d, the Duke's army entirely invested Carlisle, it being

thought proper to reduce this important key of the kingdom before the army

marched after Ascanius, into

As the army under the Duke was destitute of the artillery and

ammunition proper for a siege, it sat still before the place till the 26th,

when being amply provided with all things necessary, two batteries were raised,

which played upon the city, from the 28th to the 30th, in the morning; when the

garrison, having no prospect of relief from their friends in Scotland, and

fearing to be reduced by storm, hung out the white flag to capitulate; however,

the best terms they could obtain was, that they should not be massacred, but

reserved for the king's pleasure; which they were forced to accept, and the

English took possession of the city the same day. In this affair, besides the

men, they lost 16 pieces of ordnance, being all that Ascanius brought with him

into

The Duke had no sooner reduced this city than he invested General

Hawley with the chief command of the army, with order to march into Scotland,

and there make such opposition to the motions of Ascanius, as the future

circumstances of affairs should direct; meanwhile, the Duke returned to his

father's court, there to concert measures for entirely completing the ruin of

the adventurers.

Let us now follow the indefatigable Ascanius into

December 22d, Ascanius, who had divided his forces on the borders of

Scotland, marched with the largest body, about 4000 men, to Dumfries, where he

demanded of the inhabitants £2000 contribution money; of this £1100 was

immediately paid, and hostages for the rest. From this he moved northward on

the 23d, and the 25th arrived at Glasgow, choosing rather to take possession of

that town (of which he resolved to raise another large contribution, for its

active zeal against his party while he was in the south,) than to attempt the recovery

of Edinburgh, which the English had now put into a much better posture of

defence than it was when he took it.

Accordingly, he quartered his troops for several days upon the

inhabitants, and, before he left the city, obliged them to furnish him with

necessaries to the value of £10,000

January 3d, 1745-6,

Ascanius and the troops left

Mean while, Lieutenant General Hawley, commander in chief of the

English forces in Scotland, was assembling a strong, though not numerous army,

in the neighbourhood of Edinburgh, and having all things in order, he

determined to march to the relief of Stirling castle; but first he detached

Brigadier General Huske, (who was next in command under Hawley) with part of

the army, to dislodge the Earl of Kilmarnock from Falkirk, where he lay with

the young Adventurer's horse, and which, being of little use in a siege, he

posted at this town, which lies in the direct road from Edinburgh to Stirling.

On the first intelligence of Huske's approach, Kilmarnock retired to the rest

of the army at Stirling, not having forces enough to engage the Brigadier

General's troops; and thus the road being opened, the whole English army

marched to

Ascanius's affairs, not now in the same situation as when he was

in England, encircled by the English, and without the least prospect of any

reinforcements in case of a defeat, it was the highest prudence in him to avoid

an engagement, and retire into Scotland before his retreat was cut off; but now

at the head of a body of resolute fellows, elate and re-animated by their

successful retreat, the fresh troops which had joined them, and the absence of

the Duke from the English army, of which he was the very life and soul, he had

little to fear as to the event of an engagement; he doubted not his troops in

their own country, in which they had already been so successful, and in which

he foresaw so many ways of retrieving the loss of a battle.

Hawley's design was to have attacked Ascanius, who, being sensible of

the difference betwixt an army's attacking and being attacked, and of the usual

disadvantage in the latter case, resolved to give the English battle, without

giving them time to choose their ground. This he did with great success, on the

17th in the afternoon. The field of battle was the moor of

The English army, though formed in a hurry, advanced in good order,

the dragoons on the left, and the infantry in two lines. When the adverse

parties came within little more than musket-shot of each other. Hawley ordered

the dragoons to fall on sword in hand, and the foot to advance, at the same

time to give the adventurers a close fire. But before they could execute these

directions, a smart fire from the latter put the dragoons into some disorder,

and at the same time the English battalions, firing without orders, increased

the confusion; and the dragoons falling in upon the foot, occasioned their

making only one irregular fire before they began to retreat. Barrel's and

Ligoniers’ regiments, however, were immediately rallied by Brigadier

Cholmondely, and Colonel Ligoniers. These troops made a brave stand, and

repulsed the adventurers, who poured upon them very briskly. Mean time, General

Huske, with great prudence and presence of mind, formed another body of foot in

the rear of the above two regiments. General Mordaunt also rallied another

corps of infantry; and, upon the whole, the English made a tolerable retreat to

the camp at

This battle cannot properly be said to have been fought out; it had

certainly been renewed, had not bad weather prevented it. The rain and wind

were violent, and rendered the firearms of little use.

The English, wanting their artillery, had no arms to oppose to the

broad swords of the Highlanders, except their bayonets. During the action the

artillery was drawn up the hill, but the owners of the draught horses, seeing

the army in disorder, rode away with the horses so that none could be found to

draw the useless cannon from the field; by which means the whole train

(except one piece, which the grenadiers of Barrel's regiment yoked themselves

to and carried off, and three others which the people at Falkirk furnished

horses to draw away) fell into the hands of the adventurers.

The English at first (after quitting the field) determined to keep

possession of their camp, and wait to see if Ascanius would attempt to dislodge

them; but the rain coming on heavy, the tents were so wet, and so much of their

ammunition spoiled, that it was judged proper to order the troops to the town

of Linlithgow that night, purely for the sake of shelter; next day they

continued their retreat, and in the evening took up their former retreat in and

about Edinburgh, where they examined into their loss, and missed more officers

in proportion than men. Thus far, all the facts I have mentioned, relating to

the memorable battle of

Narrative drawn up by Mr. Sheridan, and by him transmitted to the

kings of

"After an easy victory, gained by 8000 over 12,000, we remained

masters of the field of battle; but as it was near five o'clock before it

ended, and as it required time for the Highlanders to recover their muskets,

rejoin their colours, and form again in order, it was quite night before we

could follow the fugitives.

"On the other hand, we had no tents nor provisions; the rain

fell, and the cold sharp wind blew with such violence, that we must have

perished had we remained all night on the field of battle; and as we could not

return to our quarters without relinquishing the advantages of the victory, the

Prince resolved, though without cannon or guides, and in extreme darkness, to

attack the enemy in their camp, and the situation of it was very advantageous,

and fortified by strong entrenchments: their solders were seized with such a

panic on our approach, that they durst not stay therein, but fled towards

Edinburgh, having first set fire to their tents.

"They had the start of us by an hour, and some troops which they

left at

"Lord John Drummond commanded the left, and distinguished himself

extremely; he took two prisoners with his own hand, had his horse shot under

him, and was wounded in the left arm with a musket ball. We should likewise do

justice to the valour and prudence of several other officers, particularly Mr.

Stapleton, brigadier in his Most Christian Majesty's army, and commander of the

Irish piquets; Mr. Sullivan, quarter-master general of the army, who rallied

part of the left wing; and Mr. Brown, colonel of the guards, and one of the

aid-de camps, formerly of Major General Lalley's regiment."

Camp

at

Jan.

31, 1745-6, N.S.

On the 18th, the day after the battle, Ascanius marched his army back

to

In this siege we shall at present leave the adventurers engaged, but

without any progress, disappointed of the succours they expected from

When the news of the battle of Falkirk reached

The troops under Hawley were extremely mortified at their late

disgrace, and ardently wished for a speedy opportunity of retrieving their

honour. In order to this, they were every day busied in preparations for

marching to the relief of the gallant old Blackney, who still continued to

defend Stirling castle with courage and constancy. In a few days the English

army was in all respects in a better condition than before the action at

Falkirk; and to animate the troops still more, January 30th, the young Duke

arrived at

The active and indefatigable Duke reviewed the troops the day after

his arrival at

Next morning the English continued their march, and the officers and

soldiers eager to come to a fresh trial with the adventurers; but hardly had

they arrived when they received advice that the enemy, instead of preparing for

battle, were repassing the Forth with great precipitation; and, to confirm this

intelligence, they saw all the advanced guards retiring from their posts in

great haste and confusion. This news was soon after put out of all doubt, by

the noise of two great reports like the blowing up of magazines. Hereupon the

Duke ordered Brigadier Mordaunt to put himself at the head of the Argyleshire

troops and dragoons, and harass the adventurers in their retreat. Mordaunt

began to execute this order with all alacrity and diligence imaginable and

arrived late in the evening at

The adventurers had also left behind them all the wounded men they had

made prisoners at the battle of

As it was late when Mordaunt and his troops arrived at

On the approach of the English towards

As for the Highlanders, they were resolved to stand by him at all

hazards, and to share in his fate, let it prove ever so desperate; however, a

fresh council of war being held, the chiefs endeavoured to moderate the extreme

ardour and forlorn resolution of the less experienced Ascanius, beseeching him

not to hazard his all

upon one desperate engagement.

Among others, the Duke of Perth strenuously opposed coming to action

with the Duke, until their circumstances should become more favourable, and

until they should have a better prospect of victory. In fine, it was at last

thought expedient, to decline the battle for the present, and to march the

whole army into the Highlands, where it was not in the least to be doubted but

they should raise many recruits, and, in the end, either be able fairly to beat

the English in a pitched battle, or to harass and ruin them, by terrible

marches, fatigues, the badness of the country, and the rigour of the season,

none of which they were so able to endure as the hardy natives.

In consequence of the above resolution, Ascanius, with a sorrowful

heart, (for he little thought he should have been obliged to turn his back on

the enemy so soon after the advantage he had gained at Falkirk,) gave orders

that all the troops should quit the camp immediately, and follow the orders

that had marched to pass the Forth. This was done with all possible speed; for

the consequence might have been fatal, had they given the enemy time to come so

nigh as to fall upon their rear and interrupt their retreat. I shall now give

the reader the particulars of Ascanius's return to the

February 2d, 1746.

Having broke down the bridge at Stirling, to retard the enemy's pursuit, the

adventurers entirely quitted the neighbourhood of that town, separating

themselves into different routs, though all led to the appointed general

rendezvous in the

The same day the Duke entered Stirling, where he received the

compliments of General Blackney and the officers of the garrison on this

memorable occasion; while this young Prince was pleased to testify his extreme

satisfaction with regard to the good defence the General had made, by which a

place of so much importance had been preserved, and the designs of his

dangerous rival Ascanius defeated. Mean while, pursuant to the Duke's orders,

many hands were employed in repairing the bridge; it being intended to march

the army over it, and follow the fugitives into the mountains.

On the 3d, in the morning, Ascanius and his people quitted

February 4th, The bridge being

repaired, the army passed over, and the advanced guard, consisting of the

Argyleshire Highlanders and the dragoons, marched that night as far as Crieff,

but the foot were cantoned in and about Dumblain, where the Duke took up his

quarters that evening.

Next day the Duke's advanced guards took possession of

Ascanius was very sensible how much the news of his retreat would

alarm his friends both at home and abroad; therefore he caused several printed

papers to be dispersed, setting forth his reasons for taking this step; beside

those already mentioned, the following were assigned, viz. That as his men,

particularly the Highlanders, were loaded with the booty they had collected in

England and Scotland, it was very proper to let them convey it home, where it

might be lodged in safety; and further, that this would secure to them an

acquired property, for which they would, doubtless, fight valiantly to the

last, and be induced to stand by the Prince, not only on his account, but also

on their own; and, after so fatiguing a campaign, to allow his troops some

relaxation; after which, when well refreshed and recruited, they would not fail

to make another irruption into the Lowlands the next Spring.

Ascanius had also other reasons, which he did not think proper

publicly to divulge: he judged, that by removing the war into the Highlands,

and by spreading reports of the severities of the enemy's troops, his men would

be the better kept together, which he now found difficult to do, and would also

contribute to increase the number of his followers. He also judged, that this would

furnish his friends in

But the Duke, who had intelligence of all the enemy's motions, from

the spies he had among them, easily penetrated all their views, and took the

most proper measures for defeating them. He marched the army, by different

roads, to

He stationed the Hessian troops, and some corps of English, at the

castles of Blair and Menzies, at

Having taken these precautions, the Duke set out for

Lord Loudon was then there, with about 1600 of the new-raised men

before-mentioned. With these he marched out to fight the adventurers; but, upon

their approach, finding them much stronger than he expected, he retreated and

abandoned the town of Inverness without the loss of a man, leaving Major Grant,

with two independent companies, in the castle, with orders to defend it to the

last extremity.

These orders were, however, but indifferently obeyed, for Ascanius no

sooner appeared before the place than the hearts of the garrison began to fail,

and after a very short siege he became master of the town and castle, where he

fixed his head quarters.

Besides the 4000 troops which now lay at Inverness, Ascanius had

several detached parties abroad, and some of these falling upon several small

corps of the Duke's Highlanders, stationed about the castle of Blair, defeated

them. These successes raised the spirits of the whole party of adventurers, notwithstanding

the badness of the quarters, want of pay, scarcity of provisions, and other

inconveniences.

And now, in spite of all the difficulties Ascanius lay under, he

resolved to prosecute his design upon Fort-Augustus and Fort-William: the

former of these was accordingly attacked, in which was only three companies of

Guise's regiment, commanded by Major Wentworth, so that it was speedily reduced

and demolished; which was the fate that Fort-George (the castle of Inverness)

had already met with: a clear demonstration that Ascanius did not now think it

necessary to have a garrison in that part of the country. But being still

incommoded by Lord Loudon, who lay at the back of the adventurers, with only

the Firth of Murray between them, the Duke of Perth, the Earl of Cromarty, and

some other chiefs, resolved to attempt the surprising of Loudon, by the help of

boats, which they drew together on their side of the Firth. By favour of a fog

they executed their scheme so effectually, that, falling unexpectedly upon the

Earl's forces, they cut them off, made a good many officers prisoners, and

forced Loudon to retire with the rest out of the

But though these advantages made much noise, and greatly contributed

to keep up the spirits of Ascanius's party, yet in the end they proved but of

littler service to him. Money now was scarce with him, and supplies both at

home and abroad fell much short of his expectation; and his people began to

grumble for their pay, and demanded their arrears, which could not be speedily

satisfied; a sure presage of the ruin of his whole party. Let us now return to

the Duke, and see what he has been doing since we conducted him to

Though the rigour of the season, the badness of the roads, and the

difficulty of supporting so many men as he had under his command, were

sufficient to exercise the abilities of the most experienced general, yet the

Duke disposed them in such a manner as proved effectual, both for safety and

subsistence, and at the same time, took care to distress the adventurers as

such as possible; for the very day after he came to Aberdeen, he detached the

Earl of Ancram with 100 dragoons, and Major Morris with

March 16th, The Duke received

advice, that Colonel Roy Stuart, one of the chiefs of the adventurers, had

posted himself at Strathbogie, with

The Duke's army was cantoned in three divisions. The first line,

consisting of six battalions;

Brigadier Stapleton, of his Most Christian Majesty's forces, was sent

by Ascanius to besiege Fort-William; he had with him a large corps of the best

adventurers, and a pretty good train of artillery, and arrived at Glenevis, in

the neighbourhood of this fortress, March 3d. About this time, his detachment

took a boat belonging to the

As the siege of Fort-William was the only regular operation of that

kind which happened in the continuance of this civil war, a journal of it, as

drawn up by an officer employed in the siege, may not be unacceptable to the

reader.

JOURNAL

Of the

Siege of FORT-WILLIAM.

March 14th, The adventurers continuing in the neighbourhood

of Fort-William, and the garrison at last perceiving that they were to undergo

a siege, began to heighten the parapets of their walls, on the side where they

apprehended the attack would be made. This work lasted a whole week, and the

two faces of the bastions were raised

15th, A detachment of the garrison, with some men

belonging to the sloops of war before mentioned, went in armed boats to attempt

the destroying of Kilmady Barns, commonly called the Corpoch. Stapleton having

notice of their motions, and suspecting their intention, sent out a strong

party to frustrate it; however, the falling of the tide contributed as much as

any thing to the miscarriage of this scheme. Some firing indeed passed on both

sides, but little damage was done on either. On the side of the garrison, a

sailor was killed, and three men were wounded; the adventurers had five men wounded,

four of them mortally.

18th, The Baltimore went up towards Kilmady Barns, in

order to cover the landing of some men for a fresh attempt upon the place. They

threw some cohorn shells, and set one hovel on fire; but the king's party were,

nevertheless, prevented from landing the Adventurer's party firing upon them,

with great advantage, from behind the natural entrenchments of a hollow road or

till. The

On the 20th, several parties

of the garrison being appointed to protect their turf-diggers, frequent

skirmishes happened between them and Stapleton's people; but as both parties

skulked behind crags and rocks, so neither received any damage.

The same evening the adventurers opened the siege, discharging at the

fort, 17 royals, or small bombs, of

21st, The adventurers finding that their batteries

were too far off, erected a new one at the foot of the Cow-hill, about

22nd, The besiegers opened their battery of cannon,

from Sugar-loaf hill, consisting only of 3 guns, 6 and 4 pounders, but

discharged only 7 times, and that without doing any damage. About 12 o'clock,

the same day, General Stapleton sent a French drum to the fort, upon whose

approach, and beating a parley, Captain Scott, commander of the garrison, asked

him what he came about? The drummer answered, that General Stapleton, who commanded

the siege, by directions from Ascanius, had sent a letter to the commanding

officer of the garrison requiring him to surrender. To this Captain Scott

replied, I will receive no letters from rebels, and am determined to defend the

fort to the last extremity. The drummer returning to Stapleton with this

answer, a close bombarding ensued on both sides for some hours; but at last the

garrison silenced the besiegers, by beating down their principal battery.

However, about ten that night, they opened another bomb-battery, near the

bottom of the Cow-hill, about

23d, As soon as day light appeared, the garrison

fired 23 bombs, 2 cohorns, 2 twelve pounders, 7 six pounders, and 6 swivels, at

the besieger's batteries, some of which tore up their platforms. The

adventurers, in return, fired as briskly as they were able upon the fort, but

it did the besieged no other damage than shooting off the leg of a private

soldier.

The same day, about

24th, Neither party fired much, and the garrison

employed most part of the day in getting their supplies of provisions on shore.

25th, At day break, Captain Scott sent out a party,

to a place about six miles off, to bring in some cattle. The adventurers fired

very briskly this morning, and the garrison plied them a little with their

mortars and guns. About

26th, The garrison fired slowly at the besieger's

batteries on the hills; and, as the latter only fired from two, the former

perceived that they had dismounted the third. In the afternoon, the last

mentioned party returned with a booty of black cattle and sheep, from the

country near Ardshiels, they also brought in four prisoners, one of whom was

dangerously wounded; they had likewise burned two villages belonging to one of

the chiefs of the adventurers, with the whole estate of the unfortunate Appin.

The same night Captain Scott went out and dammed up some drains near

the walls of the fort, in hopes of rainy weather, to make a small inundation;

and with some prisoners raised the glacis, or rather parapet, to

27th, At day-break, the adventurers opened their new

battery of four embrazures, but only with 3 guns, 6 pounders, with which, however,

they fired very briskly; but the garrison plying them with their mortars and

guns, silenced one of the besieger's guns before

31st, Captain Scott ordered 12 men from each company

to march out to the crags, about

April 3d, The adventurers received orders from Ascanius

to quit the siege immediately, and to join him at

As soon as Captain Scott perceived they had turned their backs on the

fort, he detached a party which secured 8 pieces of cannon and 7 mortars, the

adventurers not having time to carry off such cumbersome moveables. the

miscarriage of this enterprize may be considered as the immediate prelude to

the many disasters which afterwards befell the adventurers, one misfortune

immediately following upon the heels of another, till their affairs became

quite desperate, and their force entirely crushed by the decisive action of

Culloden.

The reason of this sudden and hasty retreat of the adventurers from

before Fort-William, was the necessity Ascanius was under of drawing together

all his forces in the neighbourhood of

We have already observed that they were in great distress for money

and other necessaries, and waited impatiently for a supply from France, which

they hoped (notwithstanding the miscarriage of so many vessels that had been

fitted out of Scotland) would soon arrive on board the Hazard sloop, which they

had named the Prince Charles Snow, and which they had intelligence was at sea

with a considerable quantity of treasure from France, and a number of

experienced officers and engineers, who were very much wanted.

March 25th, This long-looked for

vessel arrived in

At the same time that Ascanius employed so many of his forces

attacking Fort-William, he sent another body, commanded by Lord George Murray,

to make a little attempt upon the castle of Blair, the principal seat of the

Duke of Atholl, but of no great force, and in which there was only a small garrison,

under the command of Sir Andrew Agnew; which siege, or rather blockade, Lord

George raised with the same hurry on the approach of the Earl of Crawford, with

a party of English and Hessians, as Stapleton did that of Fort-William, upon

the very same day, and from the very same motives.

Having thus, in as clear and succinct a manner possible, run through

all the operations of the adventurers, and shown how their several bodies were

drawn off, in order to join the corps under Ascanius at Inverness, and enable

him to make a stand there, in case the Duke of Cumberland should pay him a

visit on that side the Spey; let us now return to the latter, whom we left

properly disposed to march as soon as the season and roads would permit, in

hopes of putting an end to all the future hopes of Ascanius by one general and

decisive action.

The Duke's troops, notwithstanding the severity of the winter, and the

fatigues they had endured, by making a double campaign, were at the beginning

of April, so well refreshed, and in such excellent order, that they were in all

respects fit for service; and so far from apprehending any thing from the

impetuosity of the Highland adventurers, or the advantage they had in lying

behind a very deep and rapid river, that they showed the greatest eagerness to

enter upon action. But, though the Duke encouraged, and took every possible

measure to keep up this ardour in his army, yet he acted with great

deliberation, and did not move till the weather was settled, when there was no

danger that the cavalry should suffer for want of forage.

At length, April 8th, the Georgian army moved from

The noble old Lord pronounced the latter part of his speech with so

warm an emphasis, as produced a great effect on the young officers, and even

upon Ascanius: however after a long debate, it was resolved to follow the

Marquis's advice, and suffer the enemy to pass the river without opposition; in

the mean time, Ascanius prepared to attack the Duke. Nor was he disheartened by

his enemy's superior numbers, whom, however, he did not despise, though he had

already twice vanquished them; and much less did he despise the known valour

and capacity of the Duke, aspiring to no greater honour than the vanquishing of

so noble an enemy.

Early in the morning of April

12th, fifteen companies of English grenadiers, the Argyleshire and

other Highlanders of that party, and all the Duke's cavalry, advanced towards

the Spey, under the conduct of the Duke, assisted by Major General Huske. They

no sooner arrived on the banks of the river, than the cavalry began to pass it,

under cover of two pieces of cannon. Mean time, about 2000 adventurers, who had

been posted near to this part of the river, retired as the enemy passed over;

and thereupon Ascanius began to call in his out parties, as was before related.

Kingston's horse were the first that forded the river, sustained by

the grenadiers and Highlanders; the foot waded over as fast as they arrived,

and though the water was rapid, and some places so deep that it came up to their

breasts, they went through with great cheerfulness, and without any other loss

than one dragoon and four women. the Duke's army marched to

The memorable battle of Culloden was fought on the 16th of April 1746.

Ascanius had formed a design of surprizing his enemies on the 15th while they

were at Nairn, but was prevented by the vigilance and strict discipline of the

Duke. The scene of battle was a moor not far from

Account of the Battle of Culloden, drawn up by order of his Royal Highness the Duke of

We gave our men a day's halt at Nairn, and on the 16th marched,

between four and five, in four columns. The three lines of foot (reckoning the

reserve for one) were broken into three from the right, which made three

columns equal, and each of five batallions. The artillery and baggage followed

the first column on the right and the cavalry made the fourth on the left.

After we had marched about eight miles, our advanced guards composed

of about 40 of Kingston's horse, and the Highlanders led on by the

Quarter-master-general, observed the rebels at some distance making a motion

towards us on the left, upon which we immediately formed; but finding they were

still a good way from us, and that the whole body did not come forward, we put

ourselves again upon our march in our former posture, and continued it till

within a mile of them, when we formed again the same order as before. After

reconnoitering their situation, we found them posted behind some old walls and

huts in a line with Culloden-house.

As we thought our right entirely secure, General Hawley and General

Bland went to the left with two regiments of dragoons, to endeavour to fall

upon the right flank of the enemy, and

When we were advanced within

We spent about have an hour, after that in trying which should gain

the flank of the other; and, in the mean time, his Royal Highness sent Lord

Bury (son to the Earl of Albemarle) forward, to within

Mean time, General Hawley had, by the help of our Highlanders, beat

down two little stone walls, and came in upon the right flank of the enemy's

line.

As their whole first line came down to attack all at once, their right

somewhat out-flanked Barrel's regiment, which was our left, and the greatest

part of the little loss we sustained was there; but Bligh's and Semple's giving

a smart fire upon those who had out-flanked Barrel's soon repulsed them, and

Barrel's regiment and the left of Monroe's fairly beat them with their

bayonets; there was scarce a soldier or officer of Barrel's, or that part of

Monroe's which engaged, who did not kill one or two men each, with their

bayonets and their pontoons.

The cavalry, which had charged from the right and left, met in the

centre, except two squadrons of dragoons, which he missed, and they were going

in pursuit of the runaways, Lord Ancram was ordered to pursue with the horse as

far as he could; and he did it with so good effect, that a very considerable

number were killed in the pursuit.

As we were on our march to Inverness, and were near arrived there,

Major General Bland sent a small packet to his Royal Highness, containing the

terms of the surrender of the French officers and soldiers whom he found there;

which terms were no other than to remain prisoners of war at discretion. Major

General Bland had also made great slaughter, and had taken about 50 French

officers and soldiers prisoners in the pursuit. By the best calculation that

can yet be made, it is thought the rebels lost 2000 men upon the field of battle

and in the pursuit.

I have omitted the lists, annexed to the above account, as well for

the sake of brevity, as because they could not be exact at the time, but were

afterwards much enlarged. Among the French prisoners were Brigadier Stapleton,

and Marquis de Giles, (who acted as ambassador from the most Christian King to

Ascanius) Lord Lewis Drummond, and above 40 officers more, who all remained

prisoners at large in the town of

The loss on the side of the victors was but inconsiderable: The only

persons of note killed, were Lord Robert Kerr, Captain in Barrel's regiment;

Captain Grosset, of Price's; Captain John Campbell, of the Argyleshire militia;

besides these, about 50 private men were killed and 240 wounded.

The number of prisoners taken by the English in this signal victory,

were 230 French, and 440 Scots, including a very few English of the adventuring

party, who, unhappily for themselves, had continued in the army of Ascanius

till this fatal day. All the artillery, ammunition, and other military stores

of the adventurers, together with 12 colours, several standards, and amongst

them Ascanius's own, fell into the hands of the victors. The Earl of Kilmarnock

was taken in the action; Lord Balmerino, who at first was reported to be

killed, was taken soon after by the Grants, and delivered up to the English.

Four ladies who had been very active in the service of Ascanius, were likewise

taken at

Immediately after the adventurers had quitted the field, Brigadier

Mordaunt was detached with 900 of the volunteers into Lord Lovat's country, to

reduce the Frasers, and all others who should be found in arms there; and with

the like view, other detachments were sent into the estates of most of the adventuring

chiefs; which put it entirely out of Ascanius's power afterwards to get

together any considerable number of troops. In short, the adventurers who

escaped the battle, were now necessitated to separate into small parties, in

order to shift the better for themselves.

The Earl of Cromarty was not at the battle. This Lord had been ordered

by Ascanius into his own country to raise men and money. But this order proved

fatal to the Earl, who, almost at the very instant when Ascanius was defeated

at Culloden, was taken prisoner by a party of Lord Rea's men, and a few others,

who surprised his Lordship, his son Captain McLeod, and a great many other

officers, with above 150 private men; they were conveyed on board the Hound

sloop of war and carried to Inverness.

That the reader, whether Englishman, Scotsman, Frenchman, or of any

other nation, may know in what light the Georgians, in general, looked upon

this important event, I shall quote a reflection from a writer, who though a

zealous Whig, has honestly and impartially summed up and repeated, only what

was about this time remarked in almost all companies, both public and private.

"Thus, (says he) the flame of this rebellion, which, after being

smothered for a time in Scotland, broke out at last with such force as to

spread itself into England, and, not without reason, alarmed even London

itself, that great metropolis, -- was in a short space totally extinguished by

him, who gave the first check to its force, and who, perhaps alone, was capable

of performing this service to his country, his father and his king[1].

It is sufficiently known how great a hazard the person runs of displeasing him

who praises his Royal Highness, but the regard we owe to truth, justice, and

the public, obliges one on this occasion to declare, that Providence

particularly made use of him as its most proper instrument in performing this

work. He it was who revived the spirits of the people, by the magnanimity of

his own behaviour; he, without severity, restored discipline in the army; he

prudently suspended his career at Aberdeen till the troops recovered their

fatigue, and the season opened a road to victory; he waited with patience,

chose with discretion, and most happily and gloriously improved that

opportunity which blasted the hopes of the rebels, and has secured to us the

present possession and future prospect of the wisest and best-framed

constitution, administered by the gentlest and the most indulgent government

Europe can boast."

The humility, piety, and humanity! of the Duke of Cumberland, are no

less conspicuous and admirable, on this occasion, than his prowess. Humility,

when merely constitutional, is a noble qualification: the humble man is

generally esteemed by all, and he alone stands fairest for advancement. But this

quality is most excellent, when it proceeds from the fear and love of God; for

he that, sensible of his own weakness, walks in a constant dependence upon God

for every blessing, is sure of his powerful assistance, and of being exalted

above every evil in this world, and in that which is to come.

This divine and moral disposition, gives us unspeakable pleasure in

those who are eminent in life; so that, to hear or read of a great man speaking

humbly of himself, when reflecting upon the mercy and love of God, is matter of

greater joy to us, than to hear of his conquering kingdoms.

The signal mercy of our God, in delivering us from those who came to

destroy or enslave us, has caused an universal joy, some expressing it one way,

and some another; but all join in extolling the Duke of Cumberland as the

principal deliverer of his country, under God Almighty. Amidst all these

acclamations, how beautiful a scene must it be, to behold his Highness modestly

attributing all the glory to God? That this is the case, I think plainly

appears from a worthy ejaculation of

the Duke's, a little after the late engagement, which I had from good

authority.

The rebellion being now suppressed, the legislature resolved to

execute justice upon those who dared to disturb the tranquillity of their

country.

We proceed now, to give an account of the punishment of the principal

persons who embarked in such a desperate enterprise, the history whereof the

reader has heard. Amongst these, Lord Balmerino, the Earl of Kilmarnock, Lord

Lovat, and Mr. Ratcliff, make the greatest figure. Bills of indictment for high

treason were found against the Earls of Kilmarnock and Cromarty, and Lord

Balmerino. These noblemen were tried by their Peers in Westminster Hall. The

two Earls confessed their crime, but Balmerino pleaded not guilty, and moved a

point of law in arrest of judgment. The point was, that his indictment was in

the country of

The speeches made by the Earls of

THE

EARL

OF

May it please your Grace, and my Lords,

I

have already, from a due sense of my folly, and the heinousness of those crimes

with which I stand charged, confessed myself guilty, and obnoxious to those punishments

which the laws of the land have wisely provided for offences of so deep a dye;

nor would I have your Lordships to suspect, that what I am now to offer is

intended to extenuate those crimes, or palliate my offences; no, I mean only to

address myself to your Lordships' merciful disposition, to excite so much

compassion in your Lordships' breasts, as to prevail on his Grace, and this

honourable house, to intercede with his Majesty for his royal clemency.

Though

the situation I am now in, and the folly and rashness which has exposed me to

this disgrace, cover me with confusion, when I reflect upon the unsullied

honour of my ancestors; yet I cannot help mentioning their unshaken fidelity,

and steady loyalty to the crown, as a proper subject to excite that compassion

which I am now soliciting. My father was an early and steady friend to the

revolution, and was very active in promoting every measure that tended to

settle and secure the Protestant succession in these kingdoms; he not only, in

his public capacity, promoted thse events, but in his private supported them;

and brought me up and endeavoured to instill into my early years, those

revolution principles which had always been the rule of his actions.

It

had been happy for me, my Lords, that I had been always influenced by his

precepts, and acted up to his example: yet, I believe upon the strictest

inquiry it will appear, that the whole tenor of my life, from my first entering

into the world, to the unhappy minute in which I was seduced to join in this

rebellion, has been agreeable to my duty and allegiance, and consistent with

the strictest loyalty.

For

the truth of this, I need only appeal to the manner in which I have educated my

children, the eldest of whom has the honour to bear a commission under his

Majesty, and has always behaved like a gentleman; I brought him up in the true

principles of the revolution, and an abhorrence of popery and arbitrary power;

his behaviour is known to many of this honourable House, therefore, I take the

liberty to appeal to your Lordships, if it is possible that my endeavours in

his education could have been attended with such success, if I had not myself

been sincere in those principles, and an enemy to those measures which have now

involved me and my family in ruin. Had my mind at that time been tainted with

disloyalty and disaffection, I could not have dissembled to closely with my own

family, but some tincture would have devolved to my children.

I

have endeavoured as much as my capacity or interest would admit, to be

serviceable to the crown on all occasions; and, even at the breaking out of the

rebellion, I was so far from approving of their measures, or showing the least

proneness to promote their unnatural scheme, that, by my interest in

Kilmarnock, and places adjacent, I prevented numbers from joining them, and

encouraged the country, as much as possible, to continue firm to their

allegiance.

When

that unhappy hour arrived, wherein I became a party, which was not till after

the battle of Prestonpans, I was far from being a person of any consequence

amongst them. I did not buy up any arms, nor raise a single man in their

service. I endeavoured to moderate their cruelty, and was happily instrumental

in saving the lives of many of his Majesty's loyal subjects, whom they had

taken prisoners: I assisted the sick and wounded, and did all in my power to make

their confinement tolerable.

I

had not been long with them before I saw my error, and reflected with horror on

the guilt of swerving from my allegiance to the best of sovereigns; the

dishonour that it reflected upon myself, and the fatal ruin which it

necessarily brought upon my family. I then determined to leave them, and submit

to this Majesty's clemency, as soon as I should have an opportunity: for this I

separated from my corps at the battle of Culloden, and stayed to surrender

myself a prisoner, though I had frequent opportunities, and might have escaped

with great ease; for the truth of which I appeal to the noble person to whom I

surrendered.

But,

my Lords, I did not endeavour to make my escape[2],

because the consequences in an instant appeared to be more terrible, more

shocking, than the most painful, or most ignominious death; I chose therefore

to surrender, and commit myself into the king's mercy, rather than throw myself

into the hands of a foreign power, the natural enemy to my country; with whom,

to have merit, I must persist in continued acts of violence to my principles,

and of treason and rebellion against my king and country.

It

was with the utmost abhorrence and detestation I have seen a letter from the

French court, presuming to dictate to a British monarch the manner how he

should deal with his rebellious subjects: I am not so much in love with live,

nor so void of a sense of honour, as to expect it upon such an intercession: I

depend only on the merciful intercession of this honourable House, and the innate

clemency of his Sacred Majesty.

But,

my Lords, if all I have offered is not a sufficient motive to your Lordships to

induce you to employ your interest with his Majesty, for his royal clemency in

my behalf, I shall lay down my life with the utmost resignation; and my last

moments shall be employed in fervent prayers for the preservation of the

illustrious house of Hanover, and the peace and prosperity of Great Britain.

EARL

CROMARTY'S SPEECH

My

Lords,

I

have now the misfortune to appear before your Lordships, guilty of an offence

of such a nature, as justly merits the highest indignation of his Majesty, your

Lordships, and the public; and it was from a conviction of my guilt, that I did

not presume to trouble your Lordships with any defence. As I have committed

treason, it is the last thing I would attempt to justify. My only plea shall

be, your Lordships' compassion, my only refuge, his Majesty's clemency. Under

this heavy load of affliction, I have still the satisfaction, my Lords, of

hoping that my past conduct, before the breaking out of the rebellion, was

irreproachable, also my attachment to the present happy establishment, both in

church and state; and, in evidence of my affection to the government, upon the

breaking out of the rebellion, I appeal to the then commander in chief of his

Majesty's forces at Inverness, and to the Lord President of the Court of

Session in Scotland, who, I am sure, will do justice to my conduct on that

occasion. But, my Lords, notwithstanding my determined resolution in favour of

the government, I was unhappily seduced from that loyalty, in an unguarded

moment, by the arts of desperate designing men. And it is notorious, my Lords,

that no sooner did I awake from that delusion, than I felt a remorse for my

departure from my duty; but it was then too late.

Nothing,

my Lords, remains, but to throw myself, my life, and my fortune, upon your

Lordships' compassion; but of these, my Lords, as to myself, it is the least

part of my sufferings, I have involved my eldest son, whose infancy and regard

to his parents hurried him down the stream of rebellion. I have involved also

eight innocent children, who must needs feel their father's punishment before

they know his guilt. Let them, my Lords, be pledges to his Majesty; let them be

pledges to your Lordships; let them be pledges to my country, for mercy; let

the silent eloquence of their grief and tears; let the powerful language of

innocent nature, supply my want of eloquence and persuasion; let me enjoy

mercy, but no longer than I deserve it; and let me no longer enjoy life than I

shall use it to deface the crime I have been guilty of. Whilst I thus intercede

to his Majesty, through the mediation of your Lordships, for mercy, let my

remorse for my guilt, as a subject; let the sorrow of my heart, as a husband,

and the anguish of my mind, as a father, speak the rest of my misery. As your

Lordships are men, feel as men, but may none of you ever suffer the smallest

part of my anguish.

But

if, after all, my Lords, my safety shall be found inconsistent with that of the

public, and nothing but my blood can atone for my unhappy crime; if the

sacrifice of my life, my fortune, and my family, is judged indispensably

necessary for stopping the loud demands of public justice; and if the bitter

cup is not to pass from me; "not mine, but they will, O God, be

done."

The

court pronounced sentence of death against the whole three; but the life of

Cromarty was spared, and his other two associates were ordered to be beheaded.

There

is something in the misfortunes of great men which generally attracts

attention: we shall not stay here to investigate the philosophic reason of

this; perhaps it arises from the contrast betwixt their grandeur and the

miseries into which they are plunged, that the generality of mankind are so

curious to be informed of every circumstance in their misfortunes. To gratify a

curiosity natural to the human mind, we shall give a particular account of the

manner of the execution of these unfortunate gentlemen, and some striking

circumstances in their behaviour immediately before their death.

The

day appointed for the execution of

The

Lords were conducted into separate apartments in the house, facing the steps of

the scaffold; their friends being admitted to see them. The Earl of Kilmarnock

was attended by the Rev. Mr. Foster, a dissenting minister, and the Rev. Mr.

Hume, a near relation to the Earl of Hume; the chaplain of the Tower, and

another clergyman of the church of England, accompanied Lord Balmerino; who, on

entering the door of the house, hearing several of the spectators ask eagerly, which is Lord Balmerino? answered smiling, I am Lord Balmerino, Gentlemen, at your

service. The parlour and passage of the house, the rails enclosing

the way from thence to the scaffold, and rails about it, were all hung with

black at the sheriffs' expense.

The

Lord Kilmarnock, in the apartment allotted to him, spent about an hour in his

devotions with Mr. Foster, who assisted him in prayer and exhortation.

After

which, Lord Balmerino, pursuant to his request, being admitted to confer with

the Earl, first thanked him for the favour, and then asked, "if his

Lordship knew of any order signed by the prince, (meaning the Pretender's son)

to give no quarter at the battle of Culloden?" On the Earl answering,

"No," the Lord Balmerino added, "Nor I neither," and

therefore it seems to be an invention to justify their own murders." The

Earl replied, "he did not think this a fair inference, because he was

informed, after he was taken prisoner at Inverness, by several officers, that

such an order, signed George Murray, was in the Duke's custody." --

"George Murray!" said Lord Balmerino, "then they should not

charge it on the Prince." Then he took his leave, embracing Lord

Kilmarnock with the same kind of noble and generous compliments, as he had used

before; "My dear Lord Kilmarnock, I am only sorrow that I cannot pay this

reckoning alone; once more farewell forever!" and returned to his own

room.

Then

the Earl, with the company, kneeled down, joining in a prayer delivered by Mr.

Foster, after which, having sat a few moments, and taken a second refreshment

of a bit of bread and a glass of wine, he expressed a desire that Lord

Balmerino might go first to the scaffold; but being informed that this could

not be, as his Lordship was named first in the warrant, he appeared satisfied,

saluted his friends, saying he should make no speech on the scaffold, but

desired the ministers to assist him in his last moments: and they, accordingly,

with other friends, proceeded with him to the scaffold. On this awful occasion,

the multitude, who had been waiting with expectation, on his first appearing on

the scaffold, dressed in black, with a countenance and demeanor[4]

testifying great contrition, showed the deepest signs of commiseration and

pity; and his Lordship, at the same time, being struck with such a variety of

dreadful objects at once, the multitude, the block, the coffin, the

executioner, and instrument of death, turned about to Mr. Hume, and said, Hume! this is terrible; though

without changing his voice or countenance.

After

putting up a short prayer, concluding with a petition for his Majesty King

George, and the Royal Family, in verification of his declaration in his speech,

his Lordship embraced and took his last leave of his friends. The executioner,

who before had something administered to keep him from fainting, was so

affected with his Lordship's distress and the awfulness of the scene, that on

asking him forgiveness, he burst into tears. My Lord bade him take courage,

giving him at the same time a purse with five guineas, and telling him he would

drop his handkerchief as a signal for the stroke. He proceeded, with the help

of his gentleman, to make ready for the block, by taking off his coat, and the bag

from his hair, which was then tucked up under a napkin-cap; but this being made

up so wide as not to keep up his long hair, the making it less occasioned a

little delay; his neck being laid bare, tucking down the collar of his shirt

and waistcoat, he kneeled down on a black cushion at the block, and drew his

cap over his eyes, in doing which, as well as in putting up his hair, his hands

were observed to shake; but, either to support himself, or as a more convenient

posture for devotion, he happened to lay both his hands upon the block, which

the executioner observing, prayed his Lordship to let them fall, lest they

should be mangled or break the blow. He was then told that the neck of his

waistcoat was in the way, upon which he rose, and, with the help of a friend,

took it off, and the neck being made bare to the shoulders, he kneeled down as

before. ----In the meantime, when all things were ready for the execution, and

the black bays which hung over the rails of the scaffold, having, by direction

of the colonel of the guard, or the sheriffs, been turned up, that the people

might see all the circumstances of the execution; in about two minutes (the

time he before fixed), after he kneeled down, his Lordship dropping his

handkerchief the executioner at once severed his head from his body, except

only a small part of the skin, which was immediately divided by a gentle

stroke: the head was received in a piece of red bays, and, with the body,

immediately put into the coffin. The scaffold was then cleared from the blood,

fresh saw dust strewed, and that no appearance of a former execution might

remain, the executioner changed such of his clothes as appeared bloody.

In

the account, said to be published by the authority of the sheriffs, it is

asserted, that the Lord Kilmarnock requested his head might not be held up as

usual, and declared to be the head of a traitor; and that, for this reason,

that part of the ceremony was omitted, as the sentence and law did not require

it: but we are assured, in Mr. Foster's account, that his Lordship made no such

request; and further, that, when he was informed that his head would be held

up, and such proclamation made, it did not affect him, and he spoke of it as a

matter of no moment. All that he wished or desired was, 1. That the executioner

might not be, as represented to his Lordship, a good sort of man, thinking a rough temper would be

fitter for the purpose. 2. That his coffin, instead of remaining in the hearse,

might be set upon the stage. 3. That four persons might be appointed to receive

the head, that it might not roll about the stage, but be speedily, with his

body, put into the coffin.

While

this was doing, Lord Balmerino, after having solemnly recommended himself to

the mercy of the Almighty, conversed cheerfully with his friends, refreshing

himself twice with a bit of bread and a glass of wine, and desired the company

to drink to him ain degrae ta

haiven, acquainting them that he had prepared a speech, which he

should read on the scaffold, and therefore should here say nothing of its

contents. The under-sheriff coming into his Lordship's apartment, to let him

know the stage was ready, he prevented him, by immediately asking, if the

affair was over with Lord Kilmarnock? and being answered, it was; he inquired, how the

executioner performed his office? and upon receiving the account, said, It was

well done; then addressing himself to the company said, Gentlemen, I shall detain you no longer;

and, with an easy, unaffected cheerfulness, he saluted his friends, and hastened

to the scaffold, which he mounted with so easy an air as astonished the

spectators. His Lordship was dressed in his regimentals, a blue coat turned up

with red, trimmed with brass buttons, (and a tye wig) the same which he wore at

the battle of Culloden; no circumstance in his whole deportment showed the

least sign of fear or regret, and he frequently reproved his friends for

discovering either upon his account. He walked several times round the

scaffold, bowed to the people, went to his coffin, read the inscription, and

with a nod, said, It is right;

he then examined the block, which he called his pillow of rest. His Lordship putting on his spectacles,

and taking a paper out of his pocket, read it with an audible voice, which, so

far from being filled with passionate invective, mentioned his Majesty as a

Prince of the greatest magnanimity and mercy, at the same time, that through

erroneous political principles, it denied him a right to the allegiance of his

people. Having delivered this paper to the sheriff, he called for the

executioner, who appearing, and being about to ask his Lordship's pardon, he

said, "Friend, you need not ask me forgiveness, the execution of your duty

is commendable," on which is Lordship gave him three guineas, saying, "Friend,

I never was rich, this is all the money I have now, I wish it were more, and I

am sorry I can add nothing to it but my coat and waistcoat," which he then

took off, together with his neck cloth, and threw them on his coffin; putting

on a flannel waistcoat which had been provided for the purpose, and then taking

a plaid-cap out of his pocket, he put it on his head, saying, he died a

Scotsman; after kneeling down at the block, to adjust his posture, and show the

executioner the signal for the stroke, which was dropping his arms, he once

more turned to his friends, took his last farewell, and looking round on the

crowd, said, "Perhaps some may think my behaviour too bold, but remember,