|

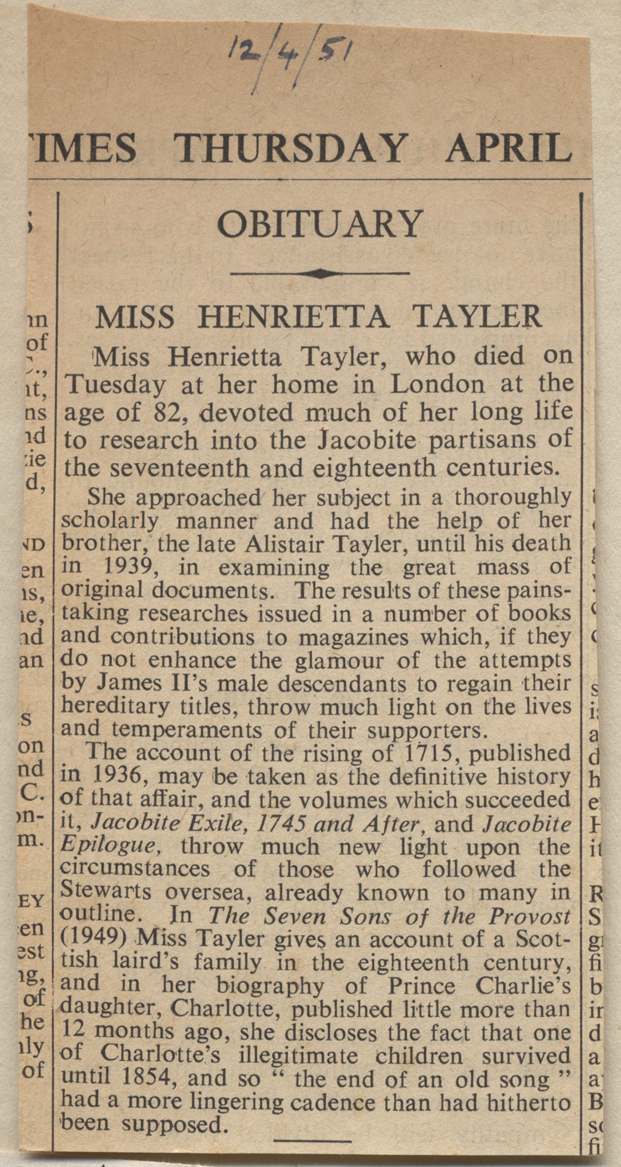

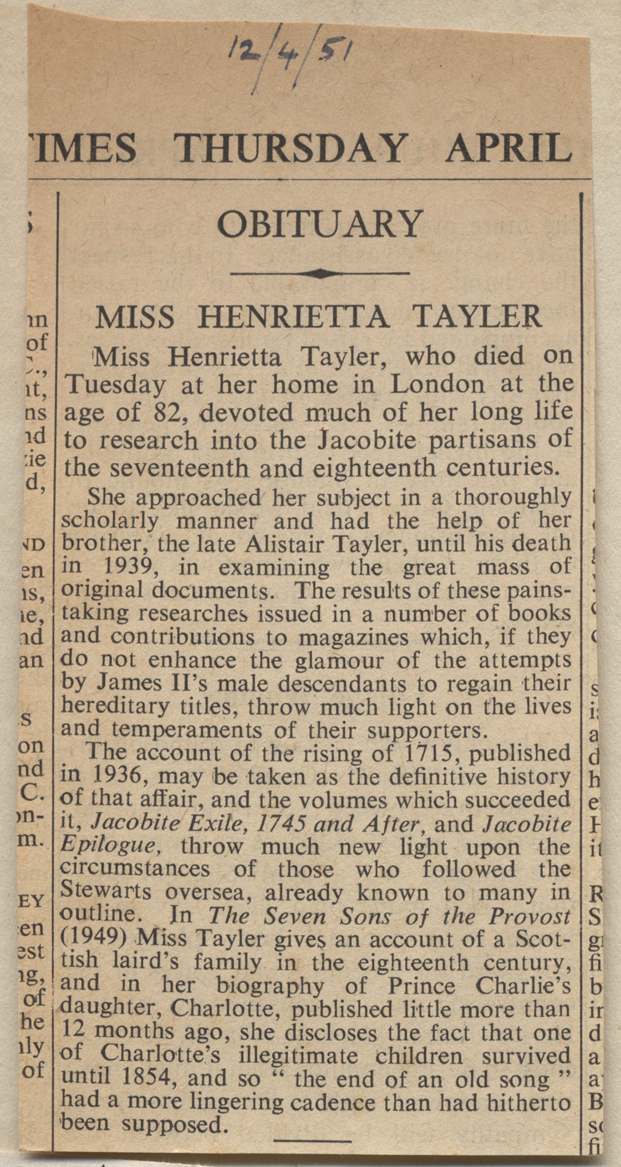

Helen Agnes Henrietta Tayler was born on 24 March 1869 in London, England. She was the daughter of William James Tayler and Georgina Lucy Duff and cousin of Dr. Walter Biggar Blaikie. She died on Tuesday, 10 April 1951 at age 82 in London, England, unmarried.

Helen Agnes Henrietta Tayler also went by the nick-name of Hetty. Worldcat lists 43 books in her name usually as co-author with her brother Alistair.

One of her books A Jacobite miscellany produced for the Roxburghe Club is very rare. All of her books are brilliantly researched and written in a very readable style from primary sources. Her understanding of French allowed her to find the, hitherto unknown, link between Charlotte Stuart and Ferdinand Maximilien Mériadec de Rohan (Prince of Rohan and Archbishop of Cambrai) which produced three illegitimate children (mes amies). One of whom may have relatives living today in Poland (Peter Pininski). Her books are all collectible items. She continued to recognise her brother Alistair as co-author long after his death. Unfortunately, only three books are currently available to read on the internet, Records of the County of Banff and The book of the Duffs volumes one and two. Here is the list of books from Google. She also wrote of her experiences as a nurse during World War I in A Scottish Nurse at Work (see a possible picture from this book below).

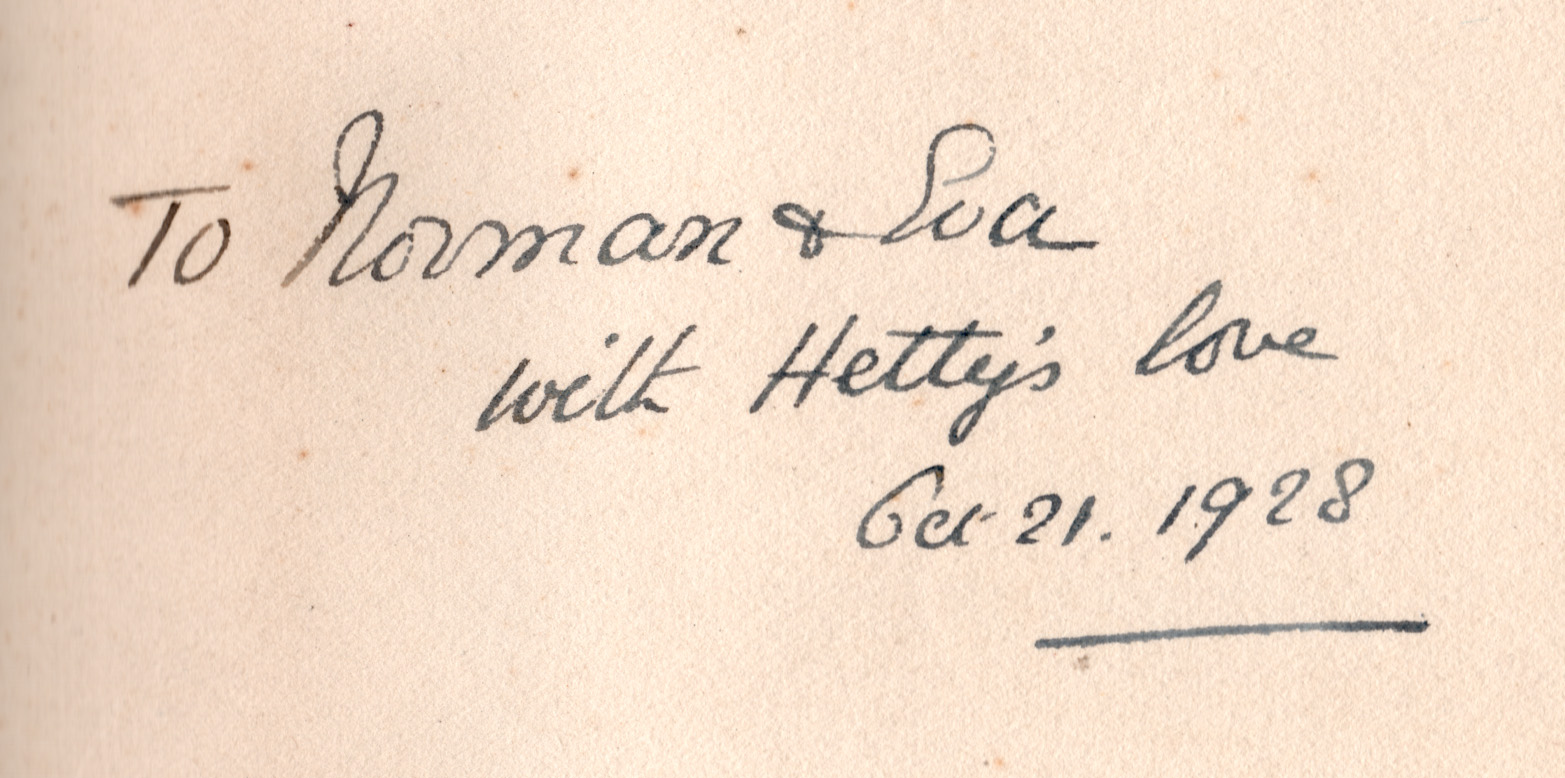

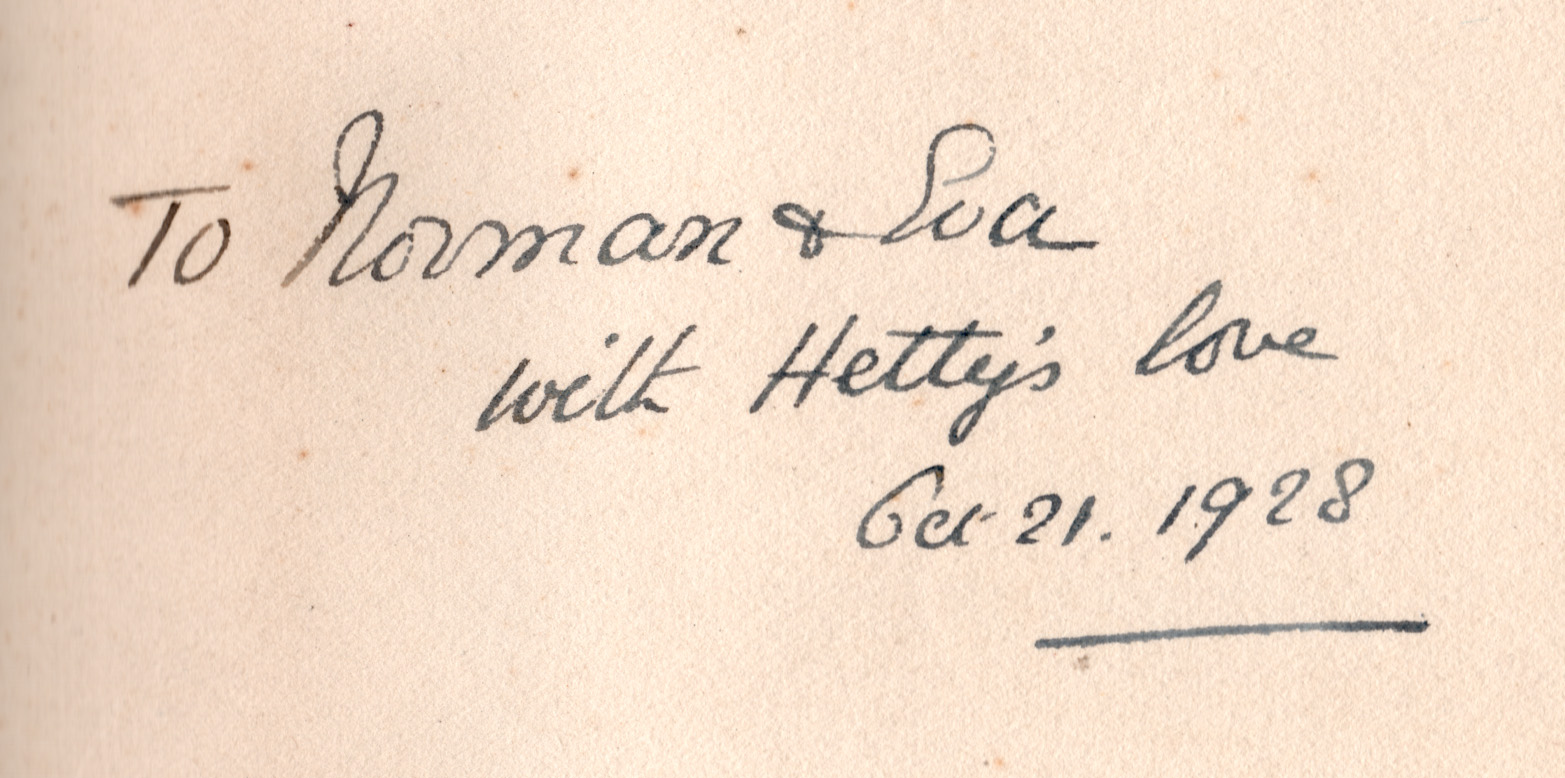

A recently purchased copy of Jacobites of Aberdeenshire & Banffshire in the Forty-Five (1928) contains her signed dedication "To Norman & Eva with Hetty's love Oct. 21, 1928."

This fitting eulogy from Sir James Fergusson of Kilkerran in Two Accounts of the Escape Prince Charles Edward is included:

I knew Hetty Tayler only since 1938, but one of the charms of knowing her was that she made you free of a life and experience which ranged extraordinarily widely in people, places, and epochs. We had many eighteenth-century acquaintances in common, and in her conversation they were just as alive as contemporaries we both knew or as the figures of her own youth, like old Mrs. Biggar, her great-grand-aunt, with whom she remembered conversing at the age of six. Mrs. Biggar’s brother was killed at Trafalgar, and their father, at the age of sixteen, fought for Prince Charlie at the skirmish of Inverurie. That was the kind of link with the past in which Hetty delighted, and her talk was full of them. She had the widest acquaintance of anyone I have ever known. ‘I always know people’s grandfathers,’ she used to say—the real significance of which remark was that her friendships, to which she must have added almost weekly, lasted literally for generations.

Born on 24 March, 1869, Hetty Tayler was of Scottish blood on both sides, but her father, William James Tayler, was a London barrister; hence her early memories were linked with Victorian Kensington as well as with the old house of Rothiemay, which last must have done much to kindle in Hetty and her beloved brother Alistair their interest in old families and family history. Their mother was a Duff, descended from Alexander, 3rd Earl Fife, and their Book of the Duffs and some other works were a pious tribute to that side of their ancestry. Their genealogical work was on the whole less distinguished than their editing of Jacobite documents; but Lord Fife and his Factor is, in my opinion, a model of how to sift and edit family letters.

Born on 24 March, 1869, Hetty Tayler was of Scottish blood on both sides, but her father, William James Tayler, was a London barrister; hence her early memories were linked with Victorian Kensington as well as with the old house of Rothiemay, which last must have done much to kindle in Hetty and her beloved brother Alistair their interest in old families and family history. Their mother was a Duff, descended from Alexander, 3rd Earl Fife, and their Book of the Duffs and some other works were a pious tribute to that side of their ancestry. Their genealogical work was on the whole less distinguished than their editing of Jacobite documents; but Lord Fife and his Factor is, in my opinion, a model of how to sift and edit family letters.

I have slipped into writing of Hetty and Alis-tair together, and that is how she would wish to be remembered. Her unpublished autobiography, which I was privileged to read, she characteristically entitled My Brother and I. She gave Alistair his full share, and perhaps more, of the credit for their joint work, and after his death in November, 1937, as long as any proportion remained of the material they had gathered in collaboration, she continued to ascribe books she had really compiled herself to the authorship of them both. One way and another, she had a hand in the publication of more than thirty books, including the miscellany volumes of the Scottish History Society and the Third Spalding Club to which she and Alistair contributed. Her tremendous energy in research was equalled only by her generosity in making its fruits available to others.

Her books’ great virtue was that they were always drawn from unpublished manuscripts, transcribed with almost too much fidelity (I used to argue quite vainly with her against her practice of reproducing ‘ye’ and ‘yt’ literatim), and illuminated by a unique familiarity with Jacobite personages and documents. Their faults were amateurish construction, occasional repetitive-ness, and too hasty writing in the narrative sections. Hetty’s free use of italics and exclamation-points in her footnotes may irritate some readers; but to her friends they will always recall her quick, staccato, discursive talk and its wealth of anecdote.

Such blemishes, anyway, hardly affect the value of her work. With her brother, she printed an immense amount of Jacobite material from the Windsor Castle archives, from family muniments, and from foreign libraries, which must place their name beside those of Chambers, Paton, and Blaikie. Their special subject was the shadow court of the exiled Stuarts and the biography of its figures; their favourite character was ‘James III.’ Their definitive history of the ‘Fifteen, their editing of O’Sullivan’s personal narrative of the ‘Forty-Five, and Hetty’s own editing of the anonymous History of the Rebellion for the Roxburghe Club would alone keep their names alive. But many, for years to come, who never read a history book, will remember Hetty as the tiny, shabby, smiling old lady who was the honorary aunt of innumerable families in Scotland and England. Multis illa bonis flebilis occidit; but she hardly knew a day’s illness, and died, on 10 April, 1951, suddenly, without pain, and in a happy hour.

|

Born on 24 March, 1869, Hetty Tayler was of Scottish blood on both sides, but her father, William James Tayler, was a London barrister; hence her early memories were linked with Victorian Kensington as well as with the old house of Rothiemay, which last must have done much to kindle in Hetty and her beloved brother Alistair their interest in old families and family history. Their mother was a Duff, descended from Alexander, 3rd Earl Fife, and their Book of the Duffs and some other works were a pious tribute to that side of their ancestry. Their genealogical work was on the whole less distinguished than their editing of Jacobite documents; but Lord Fife and his Factor is, in my opinion, a model of how to sift and edit family letters.

Born on 24 March, 1869, Hetty Tayler was of Scottish blood on both sides, but her father, William James Tayler, was a London barrister; hence her early memories were linked with Victorian Kensington as well as with the old house of Rothiemay, which last must have done much to kindle in Hetty and her beloved brother Alistair their interest in old families and family history. Their mother was a Duff, descended from Alexander, 3rd Earl Fife, and their Book of the Duffs and some other works were a pious tribute to that side of their ancestry. Their genealogical work was on the whole less distinguished than their editing of Jacobite documents; but Lord Fife and his Factor is, in my opinion, a model of how to sift and edit family letters.