IN THE HOUSE OF

GRIMALDI

BY PETER KURTH

[Note: This story is reproduced exactly as edited

and published by "Cosmopolitan" in July 1993.]

The subject on

everyone's mind in Monaco these days is marriage: Stephanie's marriage, Caroline's marriage,

Albert's marriage, even Rainier's marriage.

Since none of the ruling Grimaldi family is married at the

moment, and since the only point in having royalty (even teeny-tiny royalty

like Monaco's) is to see them behaving just like everyone else (only

more so, or less so, depending on the state of their public relations) -- well,

after ten years of bad press, bad luck, and illegitimate babies, you can

imagine it's time for some domestic tranquility. Someone in Monaco has to get married, and fast, if only to prove that

they're still in the game.

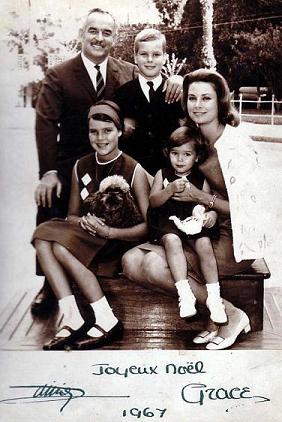

It was a wedding

that first put Monaco on the map, don't forget, in 1956, when Grace Kelly left her role as a

Hollywood princess for a new career as Europe's

most visible and dazzling Catholic grande

dame. Her death in an auto accident

in 1982 left a void in Monte

Carlo that

nothing and no one seems able to fill.

Ask anyone: Grace's tomb is the

major tourist attraction in Monaco after the palace and the casino, which pretty much

sums up her role in history and the principality at large.

"She was

superior in the same way that Peter Pan was superior," says Jeffrey

Robinson, a friend of Princess Caroline who serves as the Grimaldi family's

official biographer. Rainier himself speaks of the memory of Princess Grace as "the

motivation, true and deep, that keeps us all going.” Friends remember how "sweet" she

was before her marriage, how "lovely" and "enchanting," and

how "royal" she became with the passage of time. If, today, Rainier and his children are mentioned in the same breath with the Queen of

England as the world's most glamorous figureheads, it is thanks to Grace and to

Grace alone.

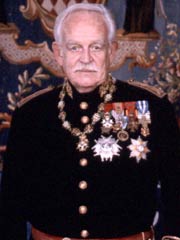

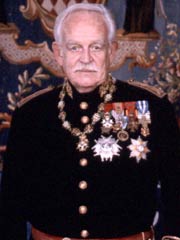

I'd better clarify

that: it's really only the children who

are glamorous. Rainier himself is a Mediterranean capitalist, the descendant of pirates, if

truth be told, who would rather watch television and eat pizza in his underwear

than attend the parties, galas, balls, and fêtes that traditionally make up the

Monaco season.

Periodically, since Grace's death, he has been linked romantically with

one or another hard-bitten socialite on the razzle-dazzle circuit (most notably

the "Business Princess," Ira von Fürstenberg),

but no one doubts that his first devotion is to the principality --

"Monaco, Inc.," 485.87 acres of porous rock and priceless sunshine

and the most valuable real estate on the French Riviera. Apart from that, the aging Prince hasn't got

a lot of "interests."

"Let's face

it," a woman I know is frank in admitting, "if Caroline, Albert and

Stephanie were to be killed in a plane crash, which God forbid, nobody would

give a damn ever again about Rainier. His face

wouldn't sell two magazines on its own.”

And don't let anyone kid you:

selling magazines -- selling Monaco -- is what it's all about. Nothing in the country would function at all

without the Prince's family to promote it, open it, close it, bless it, and be

photographed with it. In 1982, when

Grace died, the National Enquirer sent 16 reporters to Monte Carlo to cover her funeral.

Earlier, when Princess Caroline married Phillipe

Junot, the Enquirer offered $5,000 to anyone

who would sell his ticket to the ball that preceded the wedding. (No one did.) There are only a handful of

people in the world who get this kind of media attention. The Kennedys, the

Windsors, Elizabeth Taylor -- and the Grimaldis, whose problems make the lives

of the others look like fun-time in comparison.

Basically what you've got in the line of succession are a Bad Girl, a

Good Widow, and a Nice Boy on a Bobsled.

Taking the Bad Girl

first: Stephanie of Monaco -- rock star,

swimsuit designer, wannabe actress and full-time brat -- is the Problem Child

of Europe, a girl the French papers call "princesse

rockeuse" not just on account of her

up-and-down career as a pop singer. Karl

Lagerfeld once described Stephanie as "a sporty version of Madonna.” She had made Earl Blackwell's worst-dressed

list by the time she was twenty-one. She

chews her nails and likes to tell jokes -- the dirtier the better.

"What did the

elephant say to the naked man?”

Stephanie once asked a friend of her mother's at dinner, and when he

grinned and said he didn't know, she answered brightly, "Do you really eat

out of that thing?” She is

deliberately provocative, even outrageous, in her public appearances, and she

hopes to come back in some future life reincarnated as a dolphin.

"I hate being a

princess," Stephanie says -- but she relies on it, too, just as often, and

usually at the top of her voice. She is

one of those unfortunate celebrities whose garbage cans are stolen by

journalists and sifted for clues. She

throws out unused plane tickets, spare change, sedatives, and pictures of

herself; it's hard to get at the truth, of course, if you're picking through

hair mousse and globs of pasta. One of

the nicest things I've heard anybody say about Stephanie is that "she has

a lot of anger.” She's made a lot of

headlines, too, since surviving the accident that killed Princess Grace. She was only seventeen in 1982, when her

mother's Rover, with the two of them in it, plunged off the mountain road from

La Turbie on its way down to Monaco. Many believe

that Stephanie was actually driving the car, or that she and Grace were having

"a raging, slapping fight," and that one or the other of them drove

deliberately over the edge. There is

some horrible chatter indeed on the Riviera about Princess Grace's final hours. The tabloids, when they aren't making a case

for Mafia or PLO involvement in Grace's death, slyly point to suicide.

"The curve they

went over is directly above a cemetery," a reporter in Paris once told me in all seriousness. "Grace would have known that. We think she wanted to fly off to join the

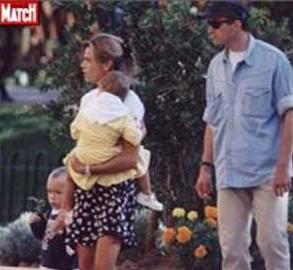

angels.” Stephanie has "had

help" in dealing with the trauma, but it's the kind of thing, obviously,

she won't ever get over. A couple of

years ago, she had a tattoo removed from an unspecified part of her body,

because it bore the name (also unspecified) of one or the other of her former

boyfriends. Now she's playing at unwed

motherhood, shacking up -- what else can I call it? -- with Daniel Ducruet, who regularly makes headlines himself by attacking

photographers, personal enemies, rival suitors, total strangers, and beating

them to a pulp.

"He's bad news,"

anyone in Monaco can tell you -- and they will, provided you swear not

to quote them by name. "Gossip was

invented in Monaco," Prince Rainier has said, but so was the happy

dictatorship, "the last oasis of peace and dreams.” If you want to live in the principality, you

have to play by the rules. There's no

other way. "And when you live

here," a friend of mine observes, "you really believe that you're

protected.”

As a matter of fact,

you are. There are 450 openly

acknowledged policemen in the principality, serving an official population that

never quite exceeds 30,000 souls. Half

of these, at any given moment, are probably somewhere else, since an awful lot

of them are millionaires, businessmen, rock stars, and socialites. Of the roughly 5000 people who are actual Monégasques (born there, and engaged in picturesque

occupations for the sake of the tourists), most earn their living from one or

another component of Prince Rainier's hugely profitable gambling, real-estate,

advertising, and corporate-convention empire.

There is no crime to speak of -- no street crime, anyway -- and no

unemployment. The principality is an

industry in the exact sense. It's a

theme park, a playground, a triumph of marketing, and a model of design. It's also a police state, where you can be

thrown out for insulting the Prince and his family when you walk down the

street in your diamonds.

"We have video

cameras in key locations around the principality," Rainier admits, "on street corners, in passageways and in public lifts. It's proven very dissuasive so we're

extending the system. Let's face it, if

a fellow sees a camera on a corner he's not going to do much because he knows

the police are watching.”

They're listening,

too. Every journalist in Monaco learns before long that his phone has been

tapped. Old hands tell stories about

operators bursting into conversations between writers and editors, shouting,

"That isn't true!” and, "How

can you say such things about the Princess!”

I went to dinner with a young man who recently opened a business in Monte Carlo, and he prefaced our conversation with the most

extraordinary warnings -- caveats I thought had gone out with the Cold

War.

"Shhhhhhh!”

he kept saying, glancing shiftily around the Café de Paris. "When you talk, talk quietly!” I was not to identify him by profession or

even nationality, because if I did, he told me, he would be

"expelled.” He was serious: "I will be out of here -- like that!” Prince Rainier has an agreement with the

French government that permits him, as an absolute monarch, to exile anyone he

pleases not just from Monaco, but, if necessary, from all four départements

of the French Riviera. Magazines and

books with a "pessimistic" view of the Grimaldis, furthermore, are

banned from the principality.

"You don't hear

a negative word about any of them," says Irish writer Genevieve Lyons, who

spends part of every summer in nearby Antibes. "People

on the Riviera -- not just Monaco -- all want Caroline or Albert or Rainier at their parties. They want

their patronage, they want to lie in their sun.

And the gossip mill functions so smoothly here that if you did

say anything nasty about them they'd hear about it before breakfast.” So nobody's saying anything nasty about

Princess Stephanie's new career as a mother.

She and Daniel Ducruet have been giving a lot

of interviews lately to say how happy they are with the baby, and how happy

Prince Rainier is to have another grandson, and how happy they're all going to

be when she and Daniel finally get married, which they will, only why rush, and

besides (this is Daniel talking), "Marriage is a beautiful ceremony which

shouldn't be overshadowed by any sense of obligation.” (Tell that to the ghost of Princess

Grace.)

"It's so sad,

so sad," says a friend of Grace's in New York. People's eyes

tend to widen when you ask about Stephanie, and royalty, in general, smacks its

collective brow at the mention of her name.

She is such an easy target for the tabloid press that it's tempting to

overlook her very real accomplishments and her winning sense of humor. It's also a fact that her lovers and

paramours, as a rule, do not discuss her when she's finished with them. They like her. They are loyal in that sense.

"I think

there's a sort of a myth at work here," says the doorman of an ultra-hot

nightclub in Paris where Stephanie sometimes appears. "Every girl in France dreams of being a princess who hangs out with

hoodlums. All of the movies are about

that, all the commercials. That's their

dream. And Stephanie lives it.”

Caroline, meanwhile,

is on to something else, slowly recovering from the terrible sorrow occasioned

by the death of her husband, Italian businessman Stefano Casiraghi,

in a speedboat accident in 1990. (Take

it from me that everyone in Monte Carlo is described as a businessman sooner or later. They're in "real estate," or

"development," or "import-export," and it all means money

-- preferably untraceable.) For most of her life before she married Casiraghi, Caroline played the same kind of circus-princess

role that Stephanie acts out now. She

was petulant, unruly, sometimes stupidly defiant and shocking. Her transformation, as one of her admirers

puts it in a shimmering image, "from slut to saint," is one of the

most interesting of our times, and she doesn't mind at all anymore when she's

compared to Princess Grace.

"I can't stand

to carry the burden of her unrealized ambition," Caroline griped about her

mother in 1978, at the ripe old age of 21.

She said many superior things in the first flush of her independence,

when she appeared as the toast of jet-set society and quite brazenly smashed

her way into marriage with the much older, cavalier, epicurean Phillipe Junot. "He works with banks," Grace remarked

(frostily, we can imagine.) Caroline tells a story now -- and it's worth

pointing out that she reveres her mother's memory -- of finding Grace one day

bent over a copy of the Almanach de Gotha, hunting for suitable sons-in-law among the

European nobility.

"Drop him or

marry him," she advised her daughter when it came to Junot,

and Caroline married him, "out of naivety," she supposes, "or

maybe in the spirit of rebellion.” Grace

was appalled at Caroline's choice of men, but she summoned enough of her

accustomed generosity to give her one of the all-time glamorous weddings of the

1970s -- an unforgettable occasion, to hear the guests tell it, when a great

deal of cocaine went up a lot of famous noses.

"Look at my

little girl," Grace cooed as Caroline tied what proved to be the loosest

of knots. "She looks just like a

princess!” (Friends, befuddled, were

obliged to answer, "She is, Gracie.

She is a princess.") By the time the Vatican, late last year, finally got around to granting

Caroline an annulment from Junot, everyone agreed

that she had paid her debt to society.

Tragedy -- sudden death -- had sobered her twice.

"Caroline is

fantastic," says Prince Dmitri of Yugoslavia, whose own family has known the Grimaldis for

years. "She's highly intelligent,

highly cultivated. She's brilliant. She can talk about anything: politics and art and metaphysics. She really is the kind of person you'd want

to have next to you at dinner.” She is

notoriously more exciting, at least in public, than her unmarried brother,

Albert, whose gifts lie more in the line of administration and

ribbon-cutting. After Grace's death,

rumors were rife that a grieving Rainier wanted to abdicate, and that Caroline (with or

without her father's consent) would "seize the throne" from

Albert. These stories, denied by the

palace as "ridiculous and completely without foundation," were rather

more dramatic than the situation warranted, but there's truth to the suspicion

that Caroline's fingers will need prying loose if and when her brother takes a

wife. There is nothing false about her

devotion to the duties she inherited from Princess Grace, nor was there

anything "sham" about her second marriage to Stefano Casiraghi. She was

heartbroken when Stefano died, pulverized with grief, and there was real

concern among her friends that she might crack under the strain of her loss.

She hasn't -- she

won't. She's taken the time to recover

for real, and all of a sudden she's smiling again, to the intense satisfaction

of the tabloids and the lace-tatting Monégasques. Caroline has had a lot of help in her

bereavement from French actor Vincent Lindon, her

boyfriend of record, who is "shadowy" in a way that differs

substantially from most of the lizards you meet in Monte Carlo. He is private. He's actually shy, and he's

completely devoted to Caroline's three children by Casiraghi,

Andrea, Charlotte, and Pierre. Lindon is also Jewish, and would presumably need to convert

to Catholicism if he wants to marry Caroline -- though why the Grimaldis,

looking at the record of royalty over the last ten years, would need to be

sticklers for protocol is beyond the ken.

It has something to do with the laws of succession, obviously: Monaco enjoys a treaty of independence with its gaping

neighbor, France, which stipulates that the Prince's family has to produce a legitimate

(i.e., a Catholic) heir, otherwise Monaco becomes French territory.

This is the upshot

of "the Albert Problem," the confusion that exists in the public mind

about the man who is frequently described as the most eligible bachelor in Europe. At 35, Albert of Monaco is handsome, athletic

(he's an Olympic bobsledder), a wee bit nervous, and as nice as the day is long

-- "the dictionary definition of nice," says a friend of the family. "He is nice, nice, nice.” Albert is the "sweetest" of all the

Grimaldis, the most like his mother, with Grace's tact and her well-known

concern for the feelings of other people.

(There is a marvelous story about Princess Grace and Diana Spencer, when

they met for the first time on the eve of Diana's marriage to the Prince of

Wales. Grace found her crying in the

ladies' room at a party and folded her in her arms. "Don't worry," she said. "It'll get worse.") For a number of

years after Grace died, Prince Rainier kept insisting he would give up his

throne as soon as Albert was "settled and confident. It will also have to do with when Albert gets

married," Rainier explained.

Albert knows that the heat is on in this regard, but so far he's refused

to succumb to the pressure. He'll take a

wife when he's ready, he says. Or

not.

"Have you

talked to any of his girlfriends?” a

friend of Grace's asked me when I called.

"Is he a homosexual?” She

thinks he isn't. She thinks that people

just think he is. "Every

time I've seen him, God knows," she says, "he's surrounded by

bimbos.” There is a fierce

protectiveness toward Albert on the part of all his family and friends, and

while everybody wants to tell you what a nice guy he is, he remains a blurry

figure, not as thrilling, somehow, as you think he might be. He's cautious, undeveloped, out of focus.

"He wants to

make you feel comfortable," says an American woman who dated Albert

in Monte Carlo. She is very

pretty, a leggy blonde, like most of his former sweethearts.

"When I went

out with him," she confides, "at nightclubs, or on his yacht,

wherever, there were lots of -- well, it's not that I think I'm lower-class,

but ... there were lots of rich people. I was never made to feel that I was less than

they were.” She was also never

encouraged to think that she might become the next Princess of Monaco: "I didn't think that anything `serious'

was going to come out of it. He didn't

try to kid me, and I respect him for that.

I feel that he will always be a good friend of mine. He will always be there for me if I need

him.” The girl explains that she

"lost it" with Albert only once, when she complained that he was hard

to reach (in the actual sense).

"I never see

you," she cried. "You're

always busy!” And Albert replied with

perfect sincerity, "But you see me more than anyone else I'm dating."

"And you know

what?” says his friend. "I believed him. I'd probably seen him all of twice that

month. But this is the thing: he never pretended with me.” She gently rejects the suggestion that Albert

might be gay. She's a professional

dancer, and she knows from homosexuals:

she "would have noticed.”

Albert himself has publicly denied the rumors about his sexuality, but

he's smart enough to realize that no denial he can make would satisfy the press

or his eager legion of gay male fans.

His photograph appears in the newspapers with astonishing regularity as

he frolics in boats and on sunlit beaches with a wide assortment of

bare-breasted girls. He's been seen on

the slopes, so to speak, in the company of Brooke Shields, Donna Rice,

Catherine Oxenberg, and, most recently, Claudia Schiffer, but again, so far as anyone knows, there's

"nobody serious" in the picture.

"And why should

there be?” asks a friend of Albert's in New York? Albert is only 35, a little older than Rainier was when he met Grace Kelly. I

asked his pal to tell me "what makes Albert tick," and the answer

came without a beat: "Girls. Girls and sports and good friends."

Is Albert gay? I blurted

out (hang the consequences!).

"I'm not going

to give you any details," his friend replied. "Let's just say I've been out with him

at night.” He added something I couldn't

catch about "bringing them home," then said: "Do you think it would be easy for

Albert to find a bride? It's one thing to marry a bimbo, it's another thing to

marry someone like his mother. She was

superb. She was the best thing that ever

happened to the principality.” There

remains the possibility that Albert is just too boring and too nice for the

shark-infested waters of Monaco, but this, as so much else, remains to be seen.

Will Albert marry?

Will Rainier abdicate? Will Caroline seize the throne? (Let's

leave Daniel and Stephanie out of it.)

"It isn't a

joke!” cried a well-known film producer

with a house in Monte

Carlo, when I

ventured that none of it mattered a damn.

"I mean" -- he was getting a bit misty -- "God bless the

principality! It's a jewel! It's a paradise! And the more the rest of the world

deteriorates, the more I realize how lucky we are. I go to church every day to pray for the

health of the Prince and his family. I

really pray that God will keep them safe and sane. Because that is my security."

And you know what? I

believed him.

www.peterkurth.com